The Schilling test, named after Dr. Robert F. Schilling, is a diagnostic procedure used to determine the cause of vitamin B12 deficiency. This deficiency can lead to pernicious anemia and other related conditions, which can have significant health impacts if left untreated.

Historically, the Schilling test has been a vital tool for clinicians to understand how the body absorbs vitamin B12 and to diagnose issues related to its absorption.

Understanding Vitamin B12 and Its Importance

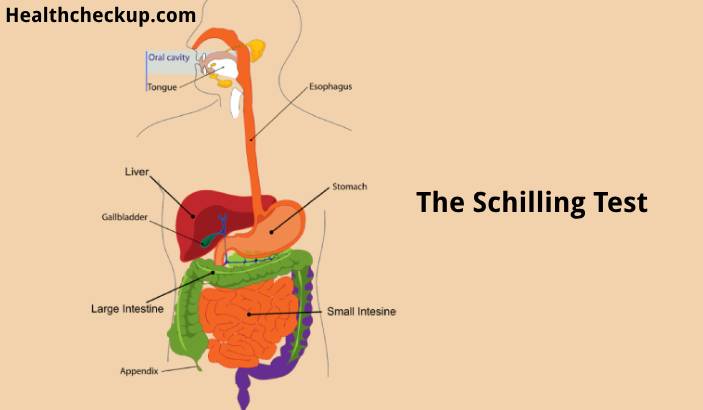

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is an essential nutrient that plays a crucial role in various bodily functions, including DNA synthesis, red blood cell formation, and neurological function. The body does not produce vitamin B12; thus, it must be obtained from dietary sources such as meat, fish, dairy products, and fortified cereals. Once ingested, vitamin B12 binds to an intrinsic factor, a protein produced in the stomach, which allows it to be absorbed in the ileum, part of the small intestine.

Why the Schilling Test is Performed?

The Schilling test is performed to diagnose the cause of vitamin B12 deficiency. This deficiency can arise from various factors, including:

- Pernicious Anemia: An autoimmune condition where the body fails to produce intrinsic factor, leading to poor absorption of vitamin B12.

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Conditions such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or surgical removal of parts of the stomach or ileum can impair vitamin B12 absorption.

- Dietary Deficiency: Insufficient dietary intake of vitamin B12, more common in strict vegetarians and vegans.

- Bacterial Overgrowth or Parasitic Infections: These can interfere with the absorption of vitamin B12 in the intestines.

The Schilling Test Procedure

The Schilling test is conducted in multiple stages to determine the specific cause of vitamin B12 deficiency. Here’s a detailed breakdown of each stage:

Stage 1: Initial Vitamin B12 Absorption

- Oral Dose: The patient is given a small oral dose of radioactive vitamin B12.

- Intramuscular Injection: A larger non-radioactive dose of vitamin B12 is injected intramuscularly shortly after the oral dose. This is done to saturate the body’s stores of vitamin B12 and ensure that any radioactive B12 found in the urine comes from the orally ingested dose.

- Urine Collection: Over the next 24 hours, the patient’s urine is collected to measure the amount of radioactive B12 excreted.

Interpretation: If the patient excretes a normal amount of radioactive B12 in their urine (typically more than 8% of the ingested dose), it suggests that vitamin B12 absorption is normal. If the excretion is low, it indicates malabsorption, necessitating further testing.

Stage 2: Intrinsic Factor Deficiency

If Stage 1 indicates malabsorption, Stage 2 is performed to check for intrinsic factor deficiency.

- Oral Dose with Intrinsic Factor: The patient is given another oral dose of radioactive vitamin B12, this time along with intrinsic factor.

- Urine Collection: Another 24-hour urine collection follows to measure the excretion of radioactive B12.

Interpretation: If the addition of intrinsic factor corrects the absorption (i.e., the excretion of radioactive B12 in urine returns to normal levels), it suggests that the patient has pernicious anemia. If absorption remains poor, it indicates a different cause of malabsorption.

Stage 3 and 4: Further Investigation

Stages 3 and 4 are less commonly performed but can provide additional information:

- Stage 3: This involves the administration of antibiotics followed by another dose of radioactive B12 to check for bacterial overgrowth as a cause of malabsorption.

- Stage 4: This stage involves the administration of pancreatic enzymes to determine if pancreatic insufficiency is affecting vitamin B12 absorption.

Clinical Significance and Utility

The Schilling test, while historically significant, is less commonly used today due to advancements in diagnostic techniques and the availability of more straightforward tests. However, it remains a valuable reference point in understanding vitamin B12 absorption mechanisms. The test helps differentiate between various causes of vitamin B12 deficiency, which is crucial for developing appropriate treatment plans.

Alternative Diagnostic Methods

Modern diagnostic approaches have largely supplanted the Schilling test due to its complexity and the need for radioactive substances. These alternatives include:

- Serum Vitamin B12 Levels: Measuring the concentration of vitamin B12 in the blood.

- Methylmalonic Acid (MMA) and Homocysteine Levels: Elevated levels of these substances can indicate vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Intrinsic Factor Antibodies: Testing for antibodies against intrinsic factor to diagnose pernicious anemia.

- Endoscopic Biopsy: Examining a biopsy of the small intestine for signs of malabsorption syndromes.

Treatment of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

The treatment for vitamin B12 deficiency depends on the underlying cause:

- Dietary Deficiency: Supplementation with oral vitamin B12 or dietary changes to include more B12-rich foods.

- Pernicious Anemia: Lifelong intramuscular injections of vitamin B12, as oral supplements are ineffective without intrinsic factor.

- Malabsorption Syndromes: Addressing the underlying condition, along with B12 supplementation, either orally in high doses or through injections.

- Bacterial Overgrowth/Parasitic Infection: Treating the infection with appropriate medications and supplementing vitamin B12.

The Schilling test, once a cornerstone in diagnosing vitamin B12 deficiency, has been largely replaced by more modern, less invasive diagnostic methods. Nevertheless, understanding the principles behind the Schilling test provides valuable insights into the complex mechanisms of vitamin B12 absorption and the various conditions that can disrupt this process. Proper diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency are essential for preventing serious health complications and ensuring optimal neurological and hematological function.

I specialize in writing about health, medical conditions, and healthcare, drawing extensively from scientific research. Over the course of my career, I have published widely on topics related to health, medicine, and education. My work has appeared in leading blogs and editorial columns.